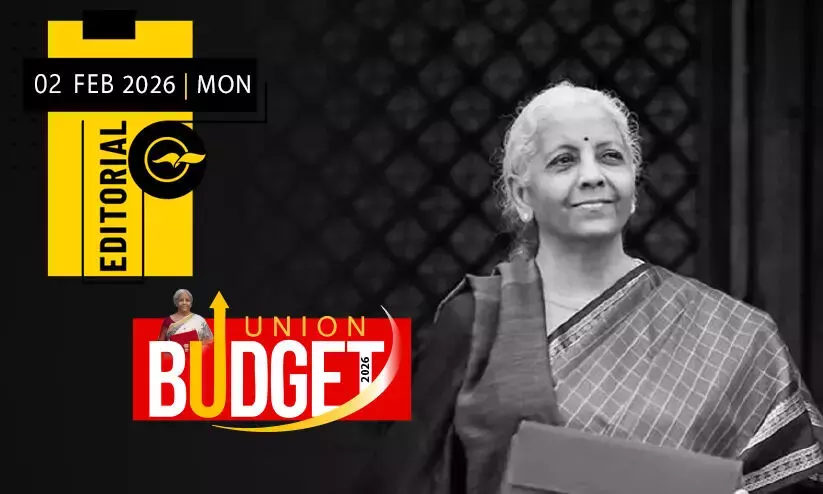

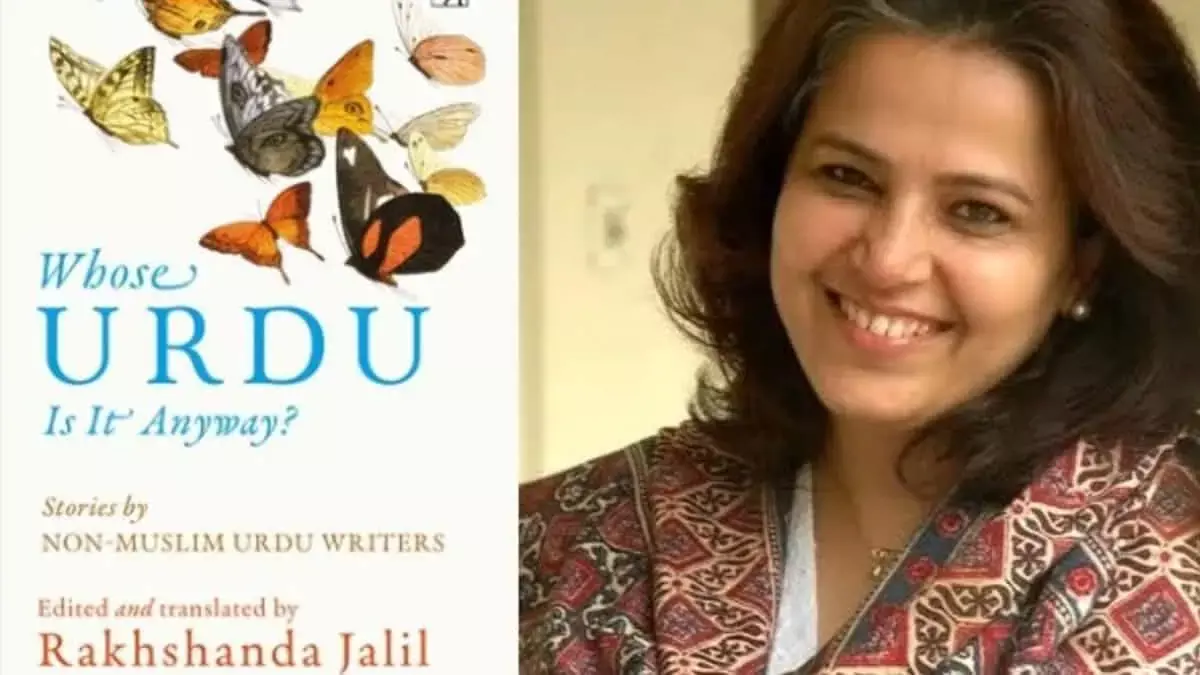

“Whose Urdu Is It Anyway?”: Rakhshanda Jalil reclaims Urdu as an Indian language

text_fieldsDr Rakhshanda Jalil, a multi-award-winning translator, writer, and literary historian, has published more than 25 books, including landmark studies of the Progressive Writers’ Movement and pioneering translations of Urdu’s greats. Her latest anthology, Whose Urdu Is It Anyway?, brings together sixteen short stories by non-Muslim writers — from Krishan Chander, Rajinder Singh Bedi, and Kanhaiyalal Kapoor to Joginder Paul, Deepak Budki, Renu Behl, and Gulzar — confronting the persistent misconception that Urdu belongs solely to Muslims. By restoring these voices to the mainstream, Jalil reclaims Urdu as a truly Indian language, born of centuries of cultural exchange and still shaping the imagination of a diverse nation. In the following edited excerpts from her interview, she discusses the language’s evolution, its contested identity, and her efforts to showcase Urdu as a politically engaged, socially meaningful literary medium.

Edited excerpts:

Urdu evolved in the subcontinent through centuries of cultural exchange, drawing from Persian, Arabic, Turkic, and local vernaculars. Could you trace how this composite language took root in India, and how, despite its shared beginnings, it eventually came to be identified almost exclusively with Muslims?

Urdu drew upon various sources for both its written and spoken form — Persian and Arabic for its script and some of its classical genres such as the ghazal and the qasida, Turkic for its vocabulary, but also Hindi for its grammar and with time incorporated so many words from not just the languages that you mention but so many “native” and “non-native” languages. Over centuries of slow incorporation, it evolved into a people’s language. As I often like to stress, Urdu is a language of the people, by the people, for the people, and therefore as Indian as anybody or anything can be regarded as Indian.

The language debate of othering Urdu and associating it with Muslims and, by extension, associating Hindi with Hindus is not new. It is well over a century old and gained momentum with eminent national figures such as Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya linking Hindi with a rising Hindu nationalism; Urdu, which had thus far been the lingua franca of undivided India, became the casualty. In the years ahead, Hindi, with its roots in Sanskrit, was linked with proponents of a muscular majoritarianism that chose to focus on the Persian and Arabic elements in Urdu instead of its rootedness in Indian soil. In present times, when everything is about optics, when fewer and fewer people make informed decisions based on real, historical events, when WhatsApp has emerged as the fount of all knowledge, Urdu is repeatedly, and erroneously, yoked with Muslims and Islam. People form opinions on the basis of stereotypes and misconceptions, and those opinions acquire the form of Gospel Truth.

Urdu was once the lingua franca of North India, cutting across communities. Today, it is increasingly seen through the lens of religion. How did this narrowing of identity take root, and what does it reveal about the intersection of language, politics, and nationalism in India?

While, on the one hand, the importance of Urdu and Urdu writers to the national mainstream is acknowledged in many ways and at different levels — with Urdu writers and poets such as Shahryar, Ali Sardar Jafri and Qurratulain Hyder being conferred the prestigious Jnanpith award, the country’s highest literary honour for a creative writer, and several noted Urdu writers being annually felicitated by the Padma awards by the Indian government — we also have a substantial number of ‘prophets of doom’, those who declare that Urdu is dead or dying. Given the extreme views, it is important to reflect on the position of Urdu in our lives today. Is Urdu confined to ‘gajals’ of dubious vintage sung by flashily-dressed singers in dimly-lit, smoke-filled rooms? How modish is it to say, “I love Urdu, especially Ghalib” when one might actually remember more Shakespeare or Wordsworth than Delhi’s pre-eminent poet? Or, how wannabe is to sway, without having a clue to its import or meaning, to the sheer sonorousness of Urdu poetry when read or recited with vim and vigour in salons and soirees? Or worse, still, must the route to mass popularity of a language and its literature necessarily lie through Bollywood studios and popular film lyrics? More importantly, what happens to a language when it is spliced from its script?

While there are no easy answers to any of the above, it is equally hard to write an obituary of Urdu. For far too long, the doomsayers have been predicting the end of Urdu and a whole way of life that accompanied it. The Urdu-Hindi debate has divided Urdu-wallahs and Hindi-wallahs into warring champions occupying opposite ends of a Great Divide, a bit like wrestlers in a wrestling pit (akhada). Yet, despite the formidable odds stacked against it, Urdu has not merely survived but flourished. Yes, fewer people read it in its own script. Yes, its propagation is not tied to employment generation. Yes, the government has paid mere lip service to safeguarding its interests. Yes, many of those who nod their heads in appreciation when they hear Urdu poetry being read or recited possibly do so because it sounds pretty rather than because they fully understand the real meaning of those mellifluous words. But that is not to say that Urdu is dead or dying. Despite the odds, Urdu has not merely survived but remained relevant. It is still the language of the heart and soul of India.

In Pakistan, Urdu was declared the national language in 1947, though it is the mother tongue of only a small minority. Did Partition create a permanent fracture in Urdu’s perception?

It is Pakistan’s internal matter and we are no one to have an opinion on whether it was right or wrong for them to declare Urdu as their national language, considering a very small proportion of the combined population of East and West Pakistan spoke Urdu at the time of their independence. But speaking for India, yes, I think this announcement accelerating the decline of Urdu in India aided and abetted with the language politics I have alluded to in your first question. So, really, it was a combination of factors: (a) willfully yoking Urdu with a people (Muslims) and a religion (Islam), (b) deliberating and purposefully positioning Hindi nationalism; (c) constantly harping on the foreignness of Urdu while conveniently ignoring its many Indian features. And there is no doubt whatsoever that with Pakistan adopting Urdu as their national language, it instantly became ‘enemy property’.

In curating stories by non-Muslim Urdu writers, you pose a radical question about ownership. To whom does a language belong? A region? A community? A religion?

My collection of 16 stories by non-Muslim Urdu writers raises precisely this question of ownership. Is Urdu the language of Muslims? Or, to be more precise, the Indian Muslims? Not to be confused with the Urdu spoken in Pakistan, which was a language smuggled in by the muhajirs and somewhat injudiciously declared the national language and adopted with much misgivings by the Punjabis, Pathans, Sindhis, not to mention Bengalis. In modern-day India, is Urdu a language of the Upper India? And within that narrow category, a declining minority of sharif Muslim families? And if we must be geographically precise, is it the language of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, for surely the effective first language of Kashmiri Muslims is Kashmiri or Laddakhi, and Muslims in the eastern parts claim Bangla or Asamiya as their mother tongue? What of the Deccan plateau, then, which was once the cradle of Urdu? Can India south of the Vindhyas lay claim to Urdu? What of the sweet cadences of the Urdu of the Malwa region or the princely states of Bhopal and Hyderabad, or even the rural hinterland of present-day Telangana, which has suffused Urdu with a lilting charm over a period of slow distillation spanning several centuries? Or, for that matter, what of Gujarat that had once boasted Wali Dakkani as a proud son of its soil? So, whose Urdu is it anyway? For far too long, the doomsayers have been predicting the end of Urdu and a whole way of life that accompanied it.

Does Urdu belong only to the poets and politicians and polemicists? Is Urdu only for the shair who sings of romance and revolution, the orator who can count upon the vim and vigour of rousing Urdu poetry to pep up the dullest of speeches, or the sloganeer who needs a catch-all ‘Inquilab Zindabad!’ or ‘Hum Dekhenge‘, or even a ‘Bol Ke Lab Azad Hain Tere…’? Is Urdu just for those who want pretty words full of sound and fury signifying nothing? Is the ‘Hindi’ film industry, located in Mumbai, the last bastion of Urdu poetry that can still reach the nooks and crannies of popular imagination? And what of Urdu prose that is so often and so unfairly overshadowed by its more glamorous twin, Urdu poetry? What of the vast treasures of Urdu fiction, creative non-fiction, its memoirs and reportage, its long history of journalism? I would like to believe Urdu is willing to belong to anyone who wants to lay claim to it.

For most non-speakers, Urdu conjures romantic images of ghazals, courtly love poetry, and an old-world elegance. What dangers lie in this romanticisation? And how do you persuade readers to encounter Urdu as a living, political, and socially engaged language?

The romanticisation and exoticisation of Urdu has done a fair bit of harm. In the process, the political muscle, the vim and vigour of the prose writers, has been overlooked, which is such a pity. In putting together anthologies such as Whose Urdu… I am also consciously trying to introduce new readers to engage with Urdu as a politically engaged, socially purposive language. In fact, I have been doing it in very many ways since working on my PhD thesis, which was published as Liking Progress, Loving Change: A History of the Progressive Writers Movement in Urdu (OUP).

In English translation, these stories not only cross linguistic borders but also cultural ones. Do you approach translation as a scholarly task, a political act, or a bridge to readers who might otherwise never encounter Urdu literature?

All of the above, though, increasingly now I see translation as a political act. People like me, literary translators, are not commercial translators; we are not translating the manual for a television set or a washing machine. Our choice of a text itself is a political decision: who we translate and why we feel it needs to be read.

How do you personally navigate being a public champion of a language caught in the crosshairs of politics?

It is challenging. I would be lying if I didn’t admit it is often disheartening. Every time I put out a post about an Urdu-related event I might be organising or a book or a translation that is about Urdu, I am told to go to Pakistan and do it! Of course, there is no point in retaliation by asking ‘Why should I?’ when Urdu is very much an Indian language, one of the 22 scheduled languages listed in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India. Why bother, you might say, but that doesn’t mean that one gets immune to the hostility. And yes, I must also admit that a certain fatigue sets in from being a relentless crusader, and you begin to ask yourself: Will the willfully blind ever see? Will the willfully deaf ever hear? But one goes on….

Beyond literature, how is Urdu surviving or fading in everyday India, in schools, signage, film, or digital spaces?

I am reminded of the late Urdu poet and his relentless optimism about the fate of Urdu in modern India. He had gone on record to say that more people appreciate Urdu poetry in India than ever before. Jaise jaise shehri tehzeeb badh rahi hai, Urdu zuban bhi badh rahi hai – he was never tired of pointing out, scoffing at those who decried the state of Urdu in India. He believed he was optimistic about India and about Urdu. He felt the government had done what it could; it was now up to the Urdu-wallahs to do the rest! Till we as a people are not proud of our language, no government can ever do enough. Admitting that he was an optimist, he told me in the course of an interview shortly before he passed away: Aaj ka din bahut achcha nahin taslim hai/Aane wale din bahut behtar hain meri rai hai (I agree that today has not been a good day/But I am convinced tomorrow will be a better day). Seeing the sprouting of Urdu-related content on various platforms — good, bad, often inaccurate — I don’t see Urdu slinking away anywhere in a hurry. I think Urdu will remain in the popular consciousness in some form or the other for a very long time.

Anything else you would like to tell our readers? An anecdote, perhaps, that drives home the idea.

I am reminded of Manto, who could always be relied upon to provide a whimsical view of the world around him. He compared the Urdu-Hindi debate raging all around him to an entirely futile debate over lemon-soda and lemon water in his essay ‘Hindi aur Urdu’: ‘Why are Hindus wasting their time supporting Hindi, and why are Muslims so beside themselves over the preservation of Urdu? A language is not made, it makes itself. And no amount of human effort can ever kill a language.”