Feeling at home where culture unites and borders divide

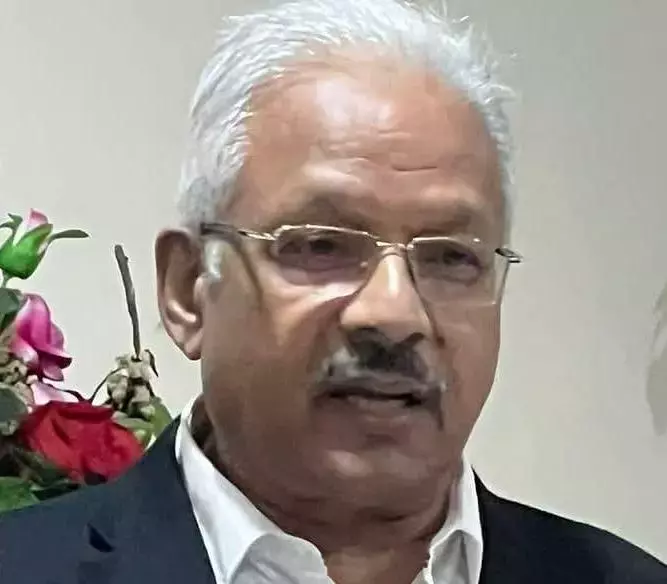

text_fieldsSam Pitroda is one of those names that instantly rings a bell in India. He is now chairman of the Indian Overseas Congress and is often in the news for making statements that trigger controversy. The ruling party loves to pounce on his words, twist them, and use them as political ammunition. But this should not make us forget his genuine contribution to the nation.

It was Pitroda who worked with Rajiv Gandhi in the 1980s to revolutionise India’s telecommunications sector. Those who are under 40 may not realise how big a change it was. In those days, getting a landline connection was almost impossible unless you had the recommendation of a Union Minister.

Today, things have changed beyond recognition. Phone companies now pester us with calls and messages offering cheaper tariffs and unlimited data. Pitroda had a key role in starting this revolution. His vision helped create the India that is now home to the cheapest data costs in the world. That legacy should not be forgotten.

Recently, Pitroda made a statement on foreign policy which, ironically, sounded very similar to what Prime Minister Narendra Modi had said in 2014. Pitroda argued that India should focus on its neighbours first, instead of looking only at global status. The idea of “Neighbourhood First” was also Modi’s slogan when he first came to power.

When Modi took oath as Prime Minister in 2014, he invited leaders of all neighbouring countries to the swearing-in ceremony. It looked almost like a coronation. Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, Sri Lanka’s President, leaders from Bangladesh, Bhutan, the Maldives and Nepal were all there. The message was clear: India was finally paying attention to its neighbourhood.

Many thought it was a refreshing break from the past. For instance, under Rajiv Gandhi, India had once even blocked petroleum supplies to Nepal in order to pressure the landlocked country. Such heavy-handed tactics created bitterness that lasted for years. Modi’s decision to visit Nepal as his very first foreign tour was therefore seen as a reaffirmation of a new friendship.

But then came the sandalwood episode. During his Nepal trip, Modi donated 2,500 kilograms of sandalwood to the Pashupatinath temple in Kathmandu. The gesture was meant to win hearts, but it raised more questions than it answered. Where did the sandalwood come from? At what cost? It turned out that it was procured from Tamil Nadu at a cost of nearly ₹1.91 crore. For a small donation, it became one of the most inquired-about gifts under the Right to Information Act. Many in Nepal and India felt that laptops or computers for Nepalese students would have been a more meaningful contribution.

The real problem is that after those early gestures, the “Neighbourhood First” policy quietly vanished. Instead, the Prime Minister began focusing on building his image as a global statesman. He visited dozens of countries, received rousing welcomes from the Indian diaspora, and promoted the idea of India as a “Vishwa Guru” — the teacher of the world.

The BJP and its ideological parent, the RSS, amplified this claim. But the reality on the ground is harder to hide. India still has the world’s largest number of illiterate people. Millions remain below the poverty line. Lofty slogans do not erase this reality.

The recent four-day conflict with Pakistan was a reminder of how far India has strayed from its neighbourhood priorities. Not a single neighbouring country expressed support for India. The government even sent MPs abroad — to places like the USA and Guyana — to explain its actions in “Operation Sindoor”. But not one delegation was sent to any South Asian neighbour. That silence spoke louder than words.

In this context, Pitroda’s comment that he felt “at home” in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal was not outrageous. He said, “I don’t feel like I’m in a foreign country. They look like me, they talk like me, they like my songs, they eat my food.” That is not politics — it is simply an observation of shared culture.

To be “at home” means to be comfortable, at ease, and familiar. Anyone who has travelled in these countries would know what Pitroda meant. I too have visited Sri Lanka, Nepal, Pakistan and Bangladesh. In Sri Lanka, the towns and villages reminded me of Kottayam, Pathanamthitta and Thiruvalla in Kerala. The landscapes resembled Munnar and Idukki. The dishes, the music, the dance, even the customs felt familiar. I really felt at home.

This does not mean I support the LTTE’s terrorism or Sri Lanka’s “Sinhala first” policy. But cultural similarities are real. In Nepal, I missed only the chaos of Delhi — the cows on the streets, the traffic indiscipline and the littering. Otherwise, it felt like home.

In Pakistan, too, I felt respected as an Indian. I have travelled to nearly 50 countries, but nowhere did I receive as much warmth as in Pakistan and even Mongolia. In Ulaanbaatar, I was respected simply because I came from the land of the Buddha, though people there did not know Buddha was born in Lumbini, now in Nepal.

I went to Pakistan as part of a group of journalists from Jammu and Kashmir. At a conference in Lahore, I was placed at the head table with President Pervez Musharraf. Our visas allowed us to visit only specific cities, but Musharraf announced that we could travel anywhere in Pakistan during our stay. That was a rare gesture.

The hospitality was overwhelming. On a flight from Lahore to Gilgit, the pilot invited each of us into the cockpit to view K-2, the second-highest peak in the world. In Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, when I missed a bus while sending a photograph to my office, a friendly journalist drove me to the next destination. I never felt unsafe.

In Lahore, we were even treated to a Kathak performance. Tarun Vijay, then editor of the RSS mouthpiece Panchjanya, was part of our delegation. He delivered a speech in Urdu and Punjabi that drew thunderous applause. Later, he admitted that he had never received such a warm response in India. He, too, felt “at home.”

Even Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee had once defied tradition by visiting the Lahore monument that commemorates the 1940 Pakistan Resolution. Modi himself once made a surprise dash to Pakistan to attend Nawaz Sharif’s family wedding. At that moment, even he must have felt at home.

There are countless smaller stories, too. A sari-clad Indian journalist who visited Pakistan was given discounts everywhere, simply because she was Indian. In another instance, when Pakistani journalists visited Chandigarh, one of them was surprised to see me, a Christian, presiding over the function at the Press Club.

In Pakistan, Christians are among the poorest, relegated to menial jobs like Dalits in India. The Sikh president of the Club explained that India was a secular nation. The Pakistani journalist admitted he could understand Hindu, Muslim or Christian, but not “secular.”

All these experiences underline one truth: we share more with our neighbours than we admit. Language, food, music, festivals, and even jokes overlap. Borders divide us, but culture unites us. That is why Pitroda’s words were not wrong. Anyone who has truly visited our neighbouring countries would have felt the same — at home.

A country is happier and safer when its neighbours are also happier. No rich person can live comfortably in a slum, however high the walls of his house. In the same way, India cannot prosper if its neighbours remain hostile or unstable. The sooner we rediscover the “Neighbourhood First” policy, the better it will be for all. After all, as Tarun Vijay, Sam Pitroda, and I have all experienced — visiting Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal or Sri Lanka often feels less like crossing a border and more like coming home.